By: Myles Herod –

Follow @MylesHerod

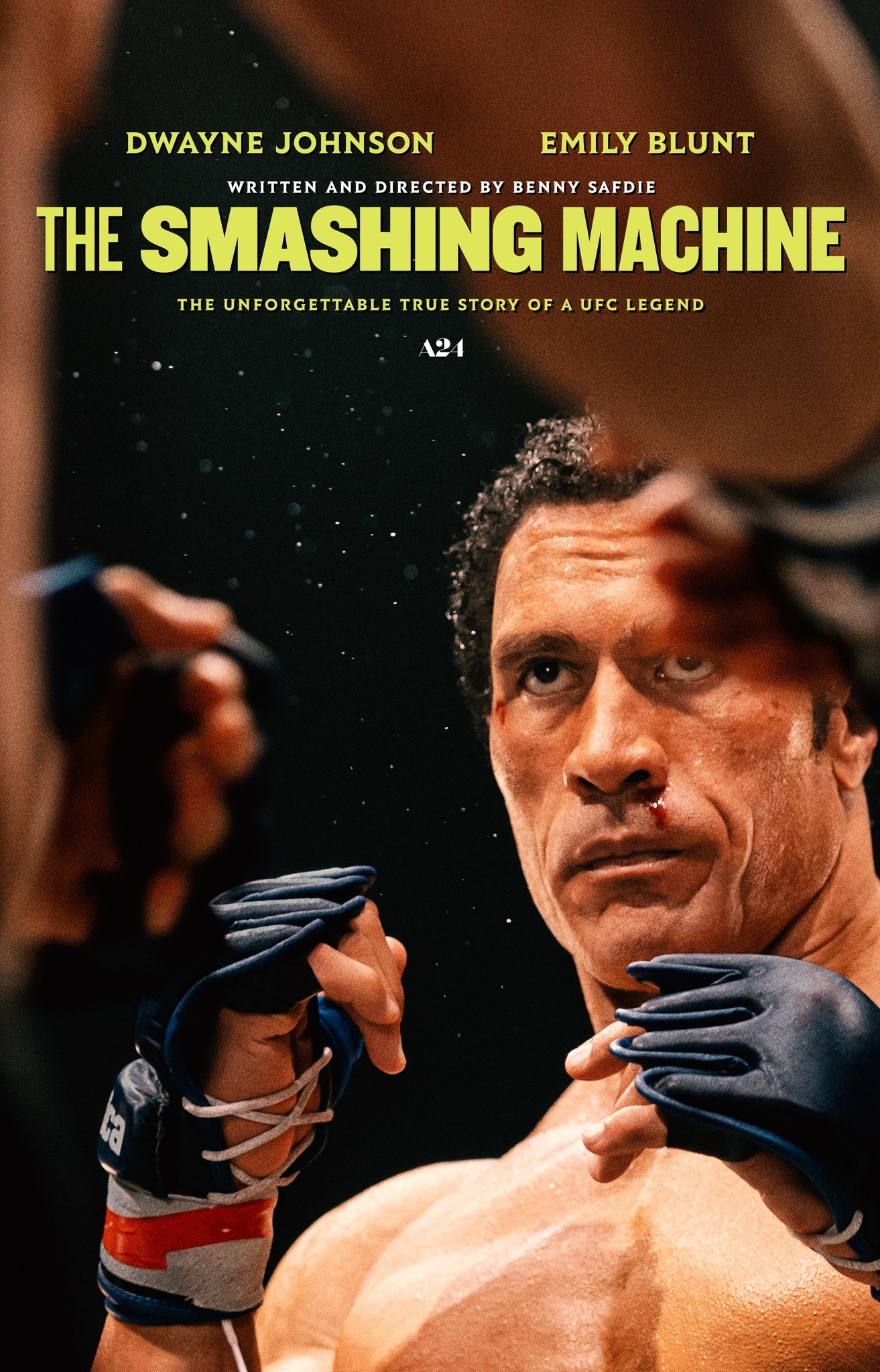

Set between 1997 and 2000, The Smashing Machine is less a sports biopic than a bruised character study, an unflinching portrait of MMA legend Mark Kerr, played with raw vulnerability by an unrecognizable Dwayne Johnson. Director Benny Safdie, stepping out from his collaborative work with brother Josh, crafts a film that resists genre tropes. Rather, it stews in favor of quiet observation. Fight scenes are framed from outside the ring, fragmented by ropes and distance. It’s a creative decision that might not work for those looking for a more visceral viewing experience, emphasizing detachment over adrenaline. Personally, I found it more effective in the film’s early stretches whereas later it begins to dilute its emotional momentum.

In those early days of MMA, the championship took place in Japan and was known as Pride, a league that demanded everything from its fighters and gave little in return. Kerr’s life outside the cage, a regimented spiral of pain management and emotional volatility, is perpetuated by his relationship with girlfriend Dawn (Emily Blunt). Their moments together are good, tender yet frayed, revealing a man whose sobriety exposes more demons than it exorcises. Blunt’s performance is quietly devastating, though her arc remains underexplored with hints of something greater.

In tone and temperament, Safdie’s direction recalls The Wrestler more than his own frenetic past (Uncut Gems), favouring melancholy over mania. I was struck by the film’s ethereal score and period-specific soundtrack, which lend a dreamlike haze to Kerr’s descent into opioid addiction. It’s a sonic texture that lingers and sometimes feels stright out of left field, amplifying the film’s emotional undercurrent, but never overwhelming. Elsewhere, his friendship with fellow fighter and trainer Mark Coleman (Ryan Bader) provides an emotional harmony: Bader’s grounded warmth contrasts Kerr’s unraveling psyche. Their bond is the film’s quiet heartbeat over 123 minutes.

If anything, Safdie favors restraint over spectacle and the film’s emotional power lies in its refusal to overstate. A late scene, Kerr, post-defeat, wandering a Japanese arena, politely protesting a kick-to-the-head rule violation, then breaking down alone, lands with quiet devastation. Johnson’s blank stare in these moments is chilling, not because it hides something, but because it might not. In the end The Smashing Machine doesn’t seek resolution. It offers reflection. It lingers in the bruises beneath the surface, asking us to sit with the ache and deciding for ourselves what remains.

Discussion

No comments yet.